Inside the Quantum Machine: How Quantum Computers Work and Why They Matter

by Scott

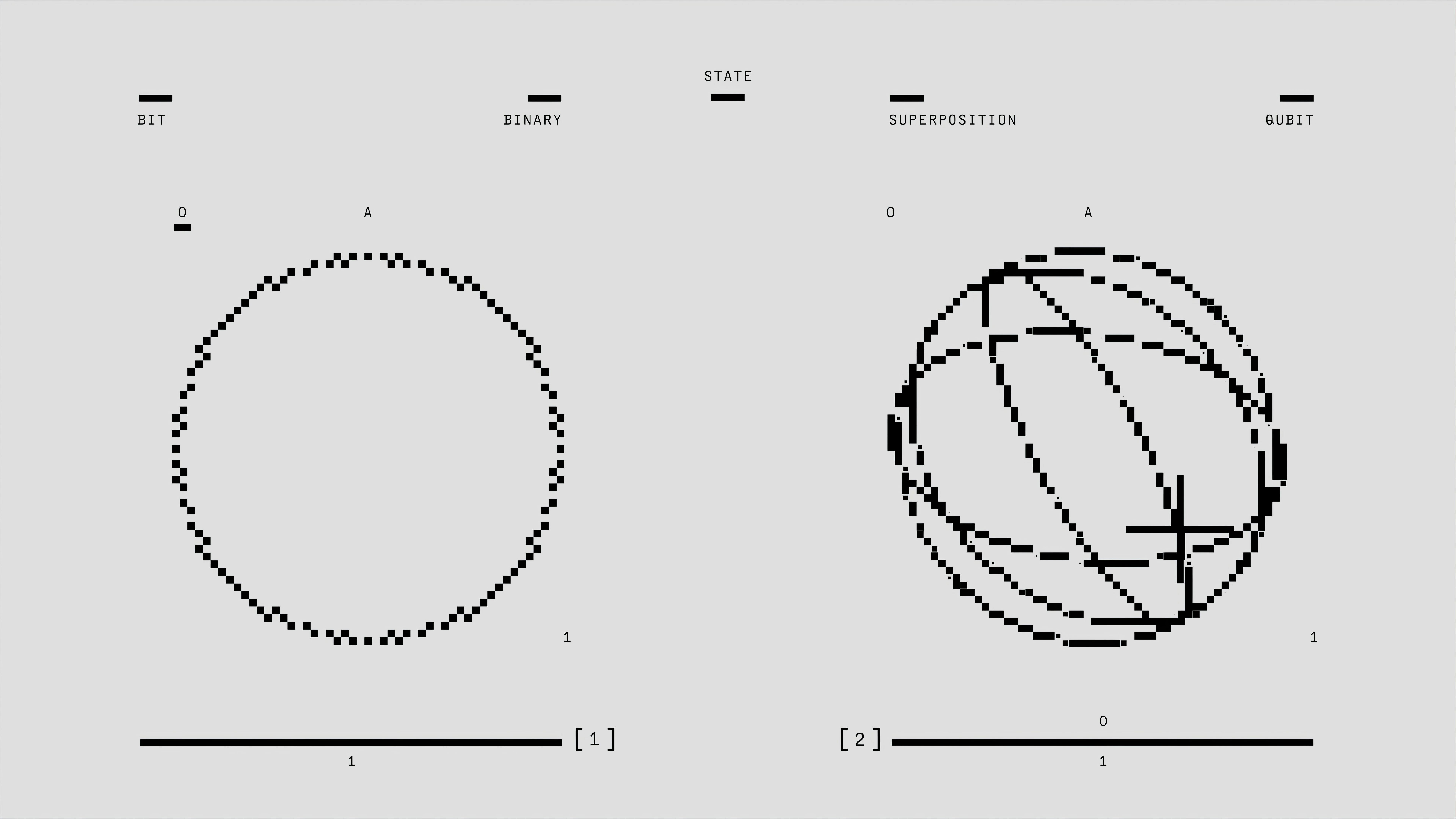

A quantum computer is a fundamentally different kind of machine from the classical computers we use every day. While traditional computers process information using bits that exist in one of two states, zero or one, quantum computers use quantum bits, known as qubits, which follow the laws of quantum mechanics. These laws allow qubits to behave in ways that feel counterintuitive but offer powerful new possibilities for computation.

The roots of quantum computing trace back to the early twentieth century, when physicists began uncovering the strange behaviour of matter and energy at very small scales. Concepts such as wave-particle duality, superposition, and entanglement challenged classical physics and reshaped scientific thinking. In the 1980s, researchers began asking whether these quantum effects could be harnessed to perform calculations. This idea laid the groundwork for quantum computing, with early theoretical work showing that certain problems could be solved exponentially faster on a quantum machine than on a classical one.

At the heart of quantum computing is the concept of superposition. Unlike a classical bit, which must be either zero or one, a qubit can exist in a combination of both states at the same time. This does not mean it holds both values in a conventional sense, but rather that its state represents a probability distribution across possibilities. When multiple qubits are combined, their superpositions interact, allowing a quantum computer to explore many potential solutions simultaneously. This parallelism is one of the key reasons quantum computers can outperform classical systems for certain tasks.

Another critical principle is entanglement. When qubits become entangled, the state of one qubit is directly linked to the state of another, even if they are physically separated. Changes to one qubit instantly affect the other. Entanglement allows quantum computers to perform coordinated operations across many qubits, dramatically increasing computational power. It also underpins emerging technologies in secure communication and distributed quantum systems.

Quantum computers today exist mostly in research labs and specialised facilities. They require extreme conditions to operate, such as temperatures near absolute zero or carefully controlled electromagnetic environments. Qubits are fragile and highly sensitive to noise, meaning even minor disturbances can introduce errors. This challenge, known as decoherence, is one of the biggest obstacles to building reliable, large-scale quantum systems. Considerable effort is being invested in error correction techniques and more stable qubit designs.

Despite these challenges, progress has been steady. Current quantum systems are already capable of performing specific calculations that would be impractical on classical computers, although they are not yet general-purpose machines. These early systems are often accessed through cloud platforms, allowing researchers and developers to experiment without needing physical hardware. This model is likely to persist, as quantum computers are expensive, delicate, and require expert maintenance.

It is unlikely that quantum computers will appear in everyday consumer devices in the foreseeable future. Their operational requirements make them poorly suited to personal electronics. Instead, quantum computing will likely exist as a specialised backend technology, accessed remotely when needed. Everyday devices may benefit indirectly, using quantum-enhanced services for optimisation, cryptography, simulation, or artificial intelligence tasks handled in the cloud.

Quantum computing has the potential to transform fields that rely on complex calculations. These include molecular modelling for drug discovery, materials science, climate modelling, financial optimisation, and logistics. Quantum systems excel at problems involving massive state spaces and intricate interactions, where classical computers struggle due to exponential complexity. In these areas, even modest quantum advantages could lead to significant breakthroughs.

Security and cryptography are also deeply affected by quantum technology. Quantum computers could eventually break many of the encryption schemes used today, prompting the development of quantum-resistant algorithms. At the same time, quantum principles enable entirely new forms of secure communication. Techniques such as quantum key distribution rely on the observer effect, where measuring a quantum system alters its state. This makes eavesdropping detectable, providing a level of security rooted in physical law rather than computational difficulty.

Other quantum principles continue to inspire new ideas. Quantum tunnelling, where particles pass through barriers they classically should not, has applications in sensing and imaging. Quantum coherence, the maintenance of stable quantum states, is being explored for ultra-precise clocks and measurement devices. These technologies may mature faster than full-scale quantum computing and find practical use sooner.

Looking ahead, quantum computing is unlikely to replace classical computing, but rather complement it. Classical systems will remain essential for everyday tasks, while quantum machines handle specific, high-impact problems. Hybrid approaches that combine classical and quantum processing are already emerging, blending the strengths of both paradigms.

In conclusion, quantum computers represent a profound shift in how we think about computation. Built on principles that challenge intuition, they offer new ways to process information and solve problems that were previously out of reach. While significant technical hurdles remain, continued progress suggests quantum technology will become a critical part of future computing infrastructure. Even if most people never interact with a quantum computer directly, its influence may shape science, security, and technology in ways that quietly transform the world behind the scenes.