How Undersea Cables Quietly Hold The World Together

by Scott

Most people imagine the internet as something abstract, floating in the air through satellites and wireless signals. In reality, the overwhelming majority of global internet traffic travels through fiber optic cables laid across the ocean floor. These undersea cables form the physical backbone of international communication. They quietly carry financial transactions, video calls, cloud data, government communications, and everyday browsing traffic between continents. Without them, the modern world would slow to a crawl.

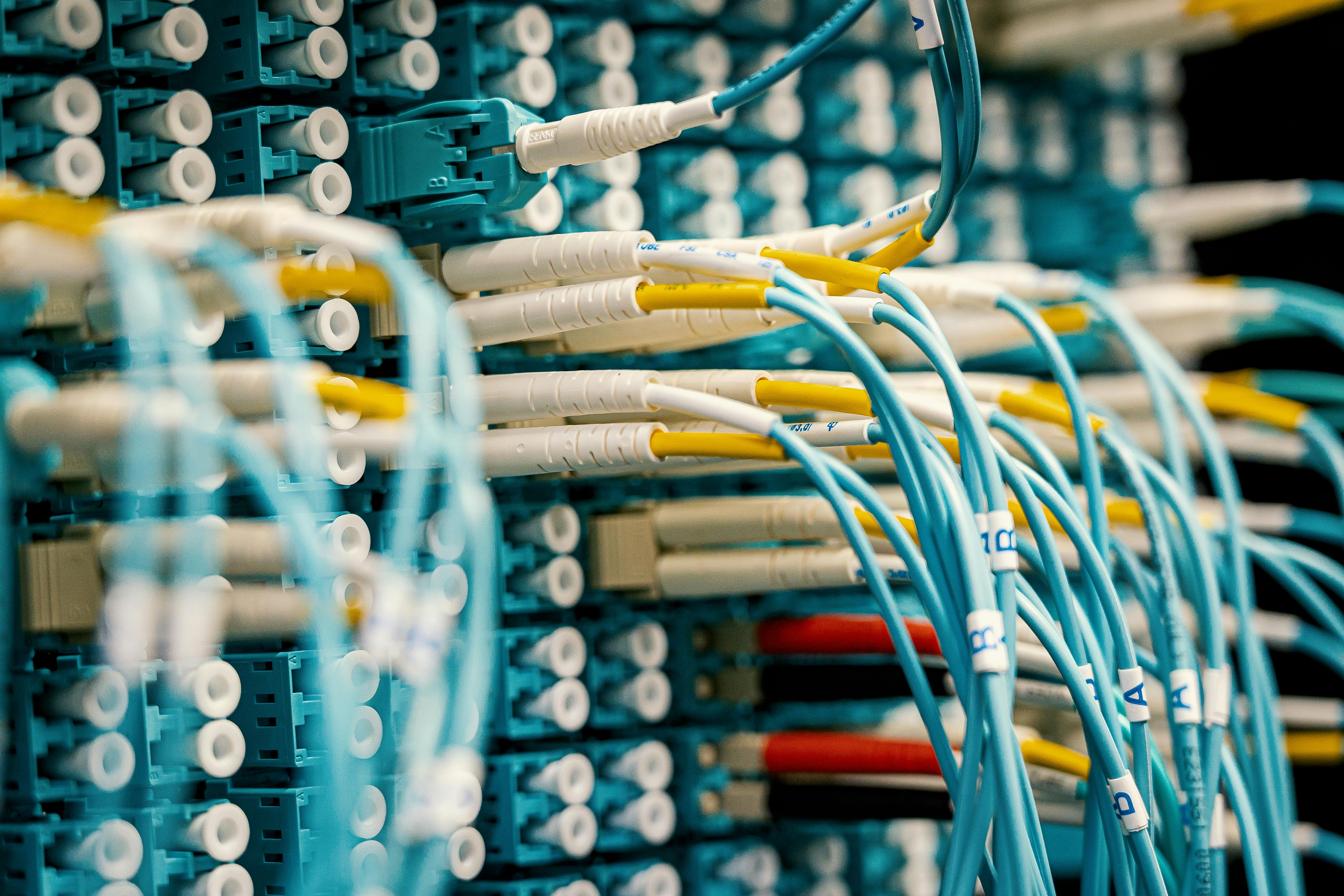

Undersea fiber optic cables are engineering projects on a massive scale. A single cable can stretch thousands of kilometers, connecting landing stations in different countries. Inside each cable are multiple fiber pairs, each capable of transmitting terabits per second of data using dense wavelength division multiplexing. Light signals are amplified at regular intervals by repeaters placed along the cable. These repeaters are powered through the cable itself using high voltage direct current supplied from shore stations. The engineering challenge is not only in transmitting data but in doing so reliably at depths that can exceed six thousand meters.

The routing of these cables is a careful process. Before a cable is laid, extensive marine surveys are conducted to map the seabed. Engineers analyze underwater topography, tectonic activity, and historical data on fishing and shipping traffic. The goal is to avoid unstable seabed areas, steep underwater slopes, and regions prone to natural hazards. In shallow coastal waters, cables are often buried beneath the seabed using specialized ploughs to protect them from anchors and trawling equipment. In deeper waters, they are typically laid directly on the ocean floor where human activity is minimal.

Cable laying ships are highly specialized vessels equipped with large spools of fiber optic cable. These ships follow precise routes determined during the planning phase. The cable is paid out slowly as the ship moves, ensuring consistent tension to prevent damage. In some regions, particularly near busy ports or fishing zones, additional protective armoring is added to the cable to increase durability. Once the cable reaches its landing point, it connects to terrestrial infrastructure through secure landing stations that house optical equipment and power feed systems.

Maintenance is a constant concern. Although undersea cables are built to last for decades, they are not immune to damage. The most common causes of faults are fishing activity and ship anchors in shallow waters. Natural events such as earthquakes and underwater landslides can also sever cables. When a break occurs, specialized repair ships are dispatched. These vessels use grappling hooks and remotely operated vehicles to retrieve the damaged section from the seabed. The broken portion is cut out, a new segment is spliced in, and the repaired cable is carefully lowered back into place. Depending on weather conditions and the location of the break, repairs can take days or even weeks.

Redundancy planning is fundamental to the resilience of global connectivity. No single cable carries all traffic between two regions. Instead, multiple parallel routes exist, often owned by different consortia of telecommunications companies and technology firms. Traffic can be dynamically rerouted if one path fails. Major internet exchange points and backbone providers constantly monitor latency and packet loss to adjust routing policies in near real time. This distributed design means that even significant cable breaks rarely result in complete outages for entire continents, though regional slowdowns can occur.

The economic implications of undersea cables are enormous. Financial markets rely on low latency connections between major trading centers. Milliseconds can translate into competitive advantage in high frequency trading. As a result, some cable routes are optimized for the shortest possible path between financial hubs. Technology companies that operate massive cloud infrastructures have increasingly invested directly in cable projects to secure bandwidth capacity and reduce dependence on third parties. This vertical integration reflects how critical raw connectivity has become to digital services.

Geopolitical tensions are closely intertwined with undersea cable infrastructure. Because cables connect sovereign territories, they pass through exclusive economic zones and territorial waters governed by international law. Control over landing points and cable ownership can influence economic leverage. Governments monitor cable security closely due to concerns about espionage and sabotage. While fiber optic signals are difficult to intercept without physical access, the landing stations and terrestrial segments represent potential points of vulnerability. As global competition intensifies, nations are more aware of the strategic value of controlling or influencing undersea communication routes.

There are also environmental considerations. Cable projects must navigate regulatory approvals related to marine ecosystems, coral reefs, and protected habitats. Although fiber optic cables themselves are relatively passive once installed, the installation process can disturb seabed environments. Engineers therefore aim to minimize ecological impact during route planning and deployment. In many cases, cables coexist with marine life for decades without significant disturbance after installation.

Security in the undersea cable ecosystem involves multiple layers. Physical security at landing stations is strict, with access controls and surveillance systems. Data traveling through the fibers is typically encrypted at higher network layers, meaning that even if the optical signal were tapped, the content would remain unintelligible without cryptographic keys. Nevertheless, there are ongoing discussions in policy circles about the vulnerability of cables to deliberate disruption. A coordinated attack on multiple cables in a single region could create economic shockwaves, particularly in areas with limited redundancy.

Another noteworthy aspect is the rapid growth in global data demand. Streaming video, cloud computing, and emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence have dramatically increased bandwidth requirements. Modern undersea cables use advanced optical amplification and coherent modulation techniques to maximize throughput. Engineers continuously upgrade terminal equipment onshore to increase capacity without replacing the entire cable. This ability to scale performance through electronics upgrades extends the economic life of the physical infrastructure.

Satellite communications often capture public imagination, but they account for only a small fraction of intercontinental traffic. Satellites are valuable for remote regions and redundancy, yet they cannot match the bandwidth and latency performance of fiber optic cables. Light traveling through fiber experiences lower latency than signals routed via geostationary satellites. For global data centers and cloud services, fiber is indispensable.

Undersea cables quietly hold the world together in a literal sense. Every international video call, cross border payment, and cloud database synchronization depends on these submerged networks. They are rarely visible, rarely discussed, and yet they underpin modern civilization. From precise seabed mapping and armored cable design to maintenance ships and geopolitical strategy, the system that connects continents is both fragile and remarkably resilient.

As digital dependence deepens, the importance of safeguarding and expanding undersea cable networks will only grow. Investment continues into new routes that bypass traditional chokepoints, improving both capacity and strategic diversity. The ocean floor, once considered a remote and empty frontier, is now one of the most critical layers of global infrastructure. It is a reminder that even in an era defined by wireless convenience and cloud abstraction, the internet remains rooted in physical engineering beneath the waves.