From CRT Screens to Servers My First Experience With Technology

by Scott

My first meaningful experience with technology did not begin with a smartphone or a modern laptop. It began in 1995, in a small computer room at my father’s business, surrounded by big white Apple towers and cathode ray tube monitors that hummed softly as they warmed up. I was young, but I was immediately fascinated. While other kids might have gravitated toward toys or television, I gravitated toward the glow of a CRT screen and the quiet whir of cooling fans. There was something magnetic about that room. Even the gas lift chairs felt like part of the experience, rolling from one workstation to another as if I were conducting important operations.

One of the first things I remember doing was adjusting the monitors. Old CRT displays rarely produced a perfectly square image when first powered on. The geometry would be slightly skewed, edges subtly curved, proportions just a little off. I would dive into the monitor controls and carefully tweak the vertical and horizontal alignment, convinced I was improving the system. It never occurred to me that these displays simply needed time to warm up before the image stabilized. To my young mind, precision mattered. I wanted the image to be perfect, squared, aligned, disciplined. In a small way, that was probably my first exposure to calibration and system optimization.

I am not sure how much practical help I offered the business in those early days, but I felt useful. A desktop cluttered with files and folders would not remain cluttered for long if I was nearby. I would reorganize everything into what I believed was a superior structure. Folders neatly grouped, icons aligned in careful grids, naming conventions that made sense to me. No one complained. Perhaps that was because each employee had their own machine in their office, so my reorganizing efforts were confined to shared or secondary systems. Or perhaps my father simply understood that curiosity needed room to breathe.

I also remember persistently asking my father to create a game shortcut in the bottom corner of the Mac OS desktop. That single corner represented a doorway into another world. To this day I have tried to remember the name of that game. It has become one of those pieces of nostalgia that feels just out of reach. I remember its audio vividly. Sharp digital tones. The sense of speed as I zoomed across a two dimensional space. I would inevitably collide with an enemy spacecraft or a floating rock. It felt like an early form of Asteroids, simple yet captivating. Those moments planted a seed. Technology was not just about spreadsheets and documents. It was about immersion, imagination, and interaction.

Customizing the wallpaper was another small ritual. Mac OS at the time allowed for patterned backgrounds and solid color combinations. I would experiment with colors and patterns as if I were conducting groundbreaking research. A carefully chosen pattern felt like a scientific achievement. The idea that I could personalize the environment made the machine feel less like an appliance and more like an extension of thought. Even then I sensed that interfaces mattered. A computer was not just its hardware. It was the experience it presented to the user.

Those Apple systems were elegant in their own way. Large white towers, solidly built, paired with matching CRT monitors. They were not especially loud or powerful by modern standards, but at the time they felt refined. They excelled at word processing and basic office productivity, which was exactly what a business machine needed to do. The operating system felt streamlined and responsive. Even as a child I could navigate menus, open applications, and move files without feeling overwhelmed. It was intuitive in a way that shaped my expectations for all future technology.

Then the business installed an Internet connection over the copper phone line. That moment changed everything. The world was no longer confined to what was physically present in the building. Suddenly information flowed in from elsewhere. Message boards and forums became accessible. I could look up images of birds and concept cars, which were personal interests at the time. I remember the sound of the modem handshake, the pauses, the waiting. Patience was required. But when a page loaded, it felt like a portal opening.

At school I began to stay ahead of the curve. I would learn about upcoming Nintendo products before many of my classmates had heard of them. I typed slowly, one key at a time with my right index finger, but speed did not matter. Access mattered. I would research game codes and cheats once I had handheld consoles of my own. With some help, I learned how to print grayscale sheets of cheat codes to share with other students. There was something deeply satisfying about retrieving information from across the world and turning it into a physical page. Digital data became tangible. It was a powerful concept.

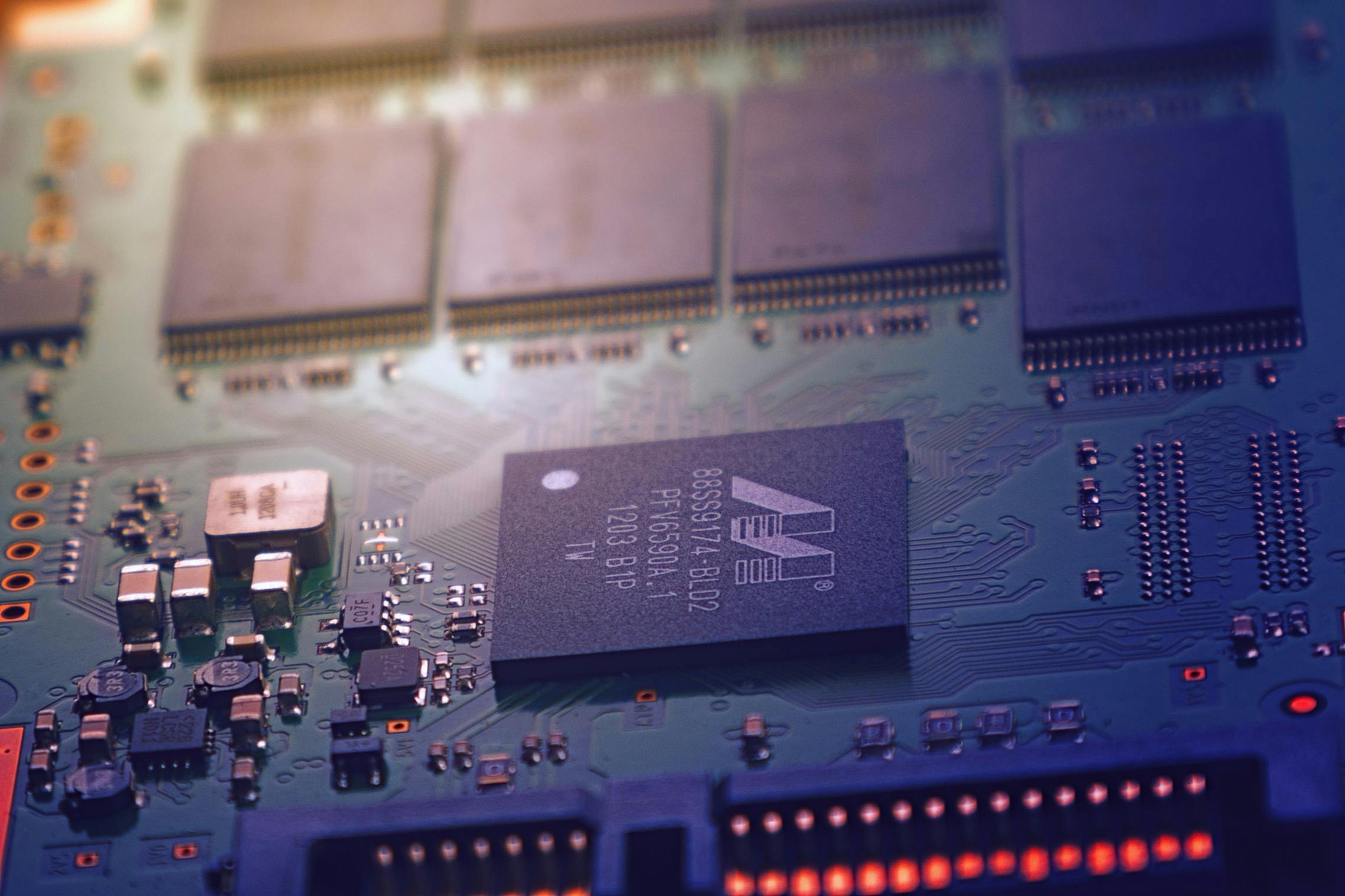

Over time the computer room itself evolved. It was gradually repurposed into a server room. A small wall mounted rack appeared, housing network switches, telephony equipment, and Internet hardware. The machines became less about visible interaction and more about silent infrastructure. Servers grew smaller and quieter. They required less frequent intervention. What once seemed mysterious became routine. Firewalls transitioned from complex manual configurations to more manageable systems that could be set and largely forgotten, only revisited for firmware upgrades or troubleshooting.

That transformation sparked a new layer of curiosity. I wanted to understand what was happening behind the scenes. How did traffic move through switches. What did a firewall actually filter. Why did a server need a restart. Eventually I stepped into performing many of the IT duties myself, all while holding a completely different role within the family business. Troubleshooting network issues, maintaining hardware, performing updates. Each task deepened my understanding.

Looking back, I realize how fortunate I was. These were production systems. They were critical to the functioning of the business. Yet my father allowed me space to explore and learn. He showed patience as I experimented, sometimes on equipment that could not afford mistakes. That trust fostered responsibility. It also solidified my fascination. Technology was no longer just a curiosity. It became a craft.

The progression from adjusting CRT geometry to managing network infrastructure mirrors the broader evolution of computing itself. From visible hardware and local applications to invisible networks and distributed systems. I experienced that shift firsthand, not through textbooks but through lived exposure. Each stage built upon the last.

Today I have come a long way from that small computer room in 1995. I understand far more about systems, networks, and software than I did as a child carefully aligning pixels on a warm monitor. Yet I still feel the same pull toward machines. The same instinct to tinker. The same satisfaction in solving technical problems.

There is still much to learn. Technology continues to evolve at a pace that demands humility. New frontiers appear constantly, whether in cloud infrastructure, security, artificial intelligence, or hardware innovation. But at the core of it all remains that early memory of glowing CRT screens and patterned wallpapers.

Those early Apple systems were not just business tools. They were catalysts. They shaped the way I think about order, precision, customization, and connectivity. They taught me that machines can be both practical and imaginative. They showed me that information can travel across the world in seconds and then be printed out in grayscale for a classroom full of curious students.

I owe a great deal to my father’s patience and to that small computer room. It was more than a workspace. It was the starting point of a lifelong relationship with technology. And even now, as systems become more abstract and less tangible, there remains a special place in my mind reserved for the technical side of me that began in 1995, quietly adjusting a CRT screen and believing it was improving the world one pixel at a time.